Review by Kaitlyn Chan

Kokila, Aug 2025

288 Pages, paperback, $17.99 CAD

ISBN: 9780593461426

Young Adult, 12+

APIDA, POC Lead, Historical Fiction

Why does his father refuse to work his way up? At the very least, why doesn’t he stay quiet? Instead it’s organize, unionize, mobilize, educate, petition, protest, strike, boycott, and so forth. It never ends. Why does he have to fight every fight? And for what? Even when it seems like the ideas are taking, the workers almost always change their minds as soon as the growers threaten to fine or fire or arrest or deport. Or, when they don’t, the growers hire thugs to swing bats and fists and crowbars to ensure the strike or boycott does not last.

Either way, the results are always the same:

Failure.

Shame.

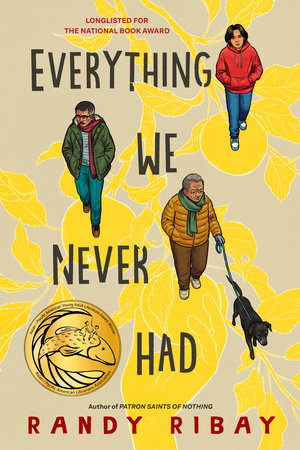

More trouble.

Randy Ribay, award-winning author of Patron Saints of Nothing, returns with another stirring novel foregrounding Filipino-American experiences. Everything We Never Had follows four generations of Filipino-American boys wrestling with their identities. As the story unfolds, the reader witnesses how societal shifts through the decades lead to disagreements between the main characters about what it means to be a “good” man, immigrant, and father.

Everything We Never Had has four main characters: Francisco, Emil, Chris, and Enzo Maghabol. Ribay writes chapters from all of their perspectives, jumping back and forth to when each was in their teenage years. The book begins in 1929 with sixteen-year-old Francisco, the first in the Maghabol family to immigrate to the United States. He works in the fields in California hoping to raise enough money to pay for his siblings’ schooling and buy back his father’s land in the Philippines. The following chapter is set in 2019–2020 from the perspective of the youngest Maghabol boy, Enzo, who finds his world turned upside down by the COVID-19 pandemic .

This immediate time jump allows readers to make connections between the two teen boys, Francisco and Enzo, who live almost a century apart. In doing so, Ribay demonstrates how the boys’ priorities may differ but, in some ways, remain the same despite the years. While Enzo might not have the same financial responsibilities as Francisco, both boys feel pressure to support and stabilize their families.

Ribay’s choice to include multiple perspectives allows the reader to understand the experiences that shape the boys’ values later in their lives. Emil, for example, shuns his Filipino heritage and discourages his son, Chris, from learning more about it. Chapters set in Emil’s teen years reveal how his own father’s activism impacted him, and how the rest of his family view the American culture. Through these third-person limited scenes, the audience can better understand Emil’s rocky relationship with his Filipino American identity.

Ribay dedicates almost equal parts to each character’s teenage years, offering a few more chapters to Francisco and Enzo who bookend the Maghabol family. In doing so, he gives the reader ample opportunity to witness how each generation influences the next. The actions of the fathers, grandfathers, and great-grandfathers manifest in the younger generations’ interests, communication styles, and values.

Everything We Never Had is an entry point to learn more about Filipino histories, including the Filipino Farm Worker Movement, Ferdinand Marcos’s dictatorial regime in the Philippines, and the rise in anti-Asian hate during the COVID-19 pandemic. While the novel cannot capture every detail of these topics, Ribay encourages young readers to continue educating themselves by including additional resources at the end of the novel.

This novel will likely resonate with first, second, or third generation immigrants who may feel a disconnect from their family members or culture. For me, the tension between the intergenerational relationships makes this story feel realistic and authentic. Ribay shares some ways to navigate these family dynamics and, by the end, readers are reminded that it will not always be easy, or even possible, to mend the rifts, but it is worth trying.

Kaitlyn Chan graduated from the University of British Columbia with a BA in English Literature and minor in Creative Writing. Fulfilling the typical stereotypes of English majors, Kaitlyn enjoys reading, writing, and tea. She spends her free time training for triathlons, singing songs in her bedroom, and trying not to buy more books.