Review by Peihwen J. Tai

Publisher: Margaret K. McElderry Books (November 4, 2025)

Length: 496 pages

CAD 30.99

ISBN13: 9781665960137

Young Adult, Ages 14+

Genre(s): Science Fiction, Dystopian

I should remember what I was doing here for my posting, but I don’t.

“Something wrong?”

I whirl around, finding a stranger standing behind me. I’m frozen for a moment, ready to

scramble for excuses and run away from this middle-aged Atahuan man.

Then he pulls his suit sleeve, adjusting its fit, and I realize it’s Nik.

“No,” I assure him. The deeper sound of my voice gives me another fright. This time I

recover quickly enough not to let it show. I go into my panel settings, erasing the existing

password and putting in a new one. Now the original user has been forced out for at least

twenty minutes. “I forgot we would be wearing different avatars.”

In the 2050s, with catastrophic sea levels and air pollution abundant, human society has moved to “upcountry,” a virtual-reality world owned by the conglomerate NileCorp.

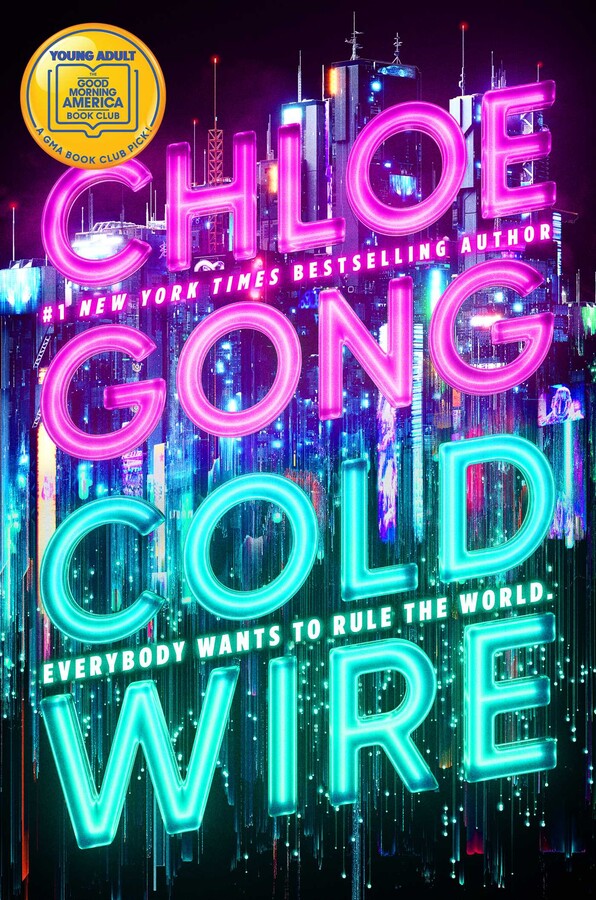

Coldwire, by Chloe Gong, follows Eirale and Lia, the two protagonists, as they navigate a dystopian world that’s, in some ways, vastly different from our own, and in others, scarily familiar. There, children are implanted with chips to give them access to the “StrangeLoom system,” a portal into upcountry.

At the start of the story, Eirale and Lia are mirrors of each other: both are ethnically Medan and each are pushed into arranged partnerships with men who initially grate on their nerves. Eirale’s matched with the anarchist terrorist, Nik Grant, while Lia has Kieren Murray, the attractive and posh Atahuan. Lia and Eirale start with very different lives, but both live in Atahua, a dominant world power in a cold war with Medaluo. Medaluo is also where Medans originate. As a Medan orphan and a state ward of Atahua, Eirale is the NileCorp corporate soldier caught in Nik’s anarchic schemes. Meanwhile, Lia is another Medan orphan adopted by the half-Medan politician Henry Sullivian, and yet, her privileged life is upended when she’s given a cryptic mission at Nile Military Academy.

Despite its high-concept world that sometimes resembled the 2014 film Lucy by Luc Besson, the core of Coldwire is the sadness embedded in the Medan protagonists, which is a minority ethnicity that takes inspiration from East Asian culture. Both Eirale and Lia are worried about proving themselves, despite already being high achievers. They’re horrified at the prospect of being treated as foreign spies or less-than, and so are desperate to overachieve. This is especially prominent in the story arc between Lia and Kieren, whom she consistently tries to one-up. There is a sobering paragraph where Lia ponders whether or not she truly had a chance to be crowned valedictorian simply because of her race. All of those sentiments mirror real-life Asian diasporic experiences, where we innately feel we need to achieve twice as much as our white peers to be treated seriously.

As refreshingly as Gong was able to put a new spin on the dystopian genre with cultural sensitivity and modern usages of fonts and formats, I found myself wishing the relationships between characters were more lived-in. At times, the banter between Eirale and Nik, or Lia and Kieren seemed stiff, cutting off the storytelling’s flow. Additionally, in the first half of the book, I was quite lost in the myriad of jargon unique to its world-building. However, towards the end of the story, I started to discover how the two protagonists are more similar than first impressions would reveal. By the end, I was utterly immersed in the story and excited to see where the series will head.

Ultimately, Coldwire remains to be one of the most interesting YA novels that I’ve read in the last five years. Dystopian YA novels often have a bad reputation for marginalizing minorities, but if I were to pinpoint the strongest aspects of Gong’s writing, I’d say they’d be her knack for surprising plot twists and her empathetic, natural focus on centring on minority experiences. With its scarily pertinent themes of identity and surveillance in the age of AI, this book is the perfect read for older teens who find themselves navigating this disorienting age of the 2020s.

Peihwen J. Tai is a Taiwanese/Canadian writer, performer, and current MFA in Creative Writing candidate at UBC. Her play Moth Boy is being produced at the University of the Fraser Valley in late 2025–directed by Tetsuro Shigematsu. She’s the first and youngest new-play-development playwright at UFV since the 1980s.